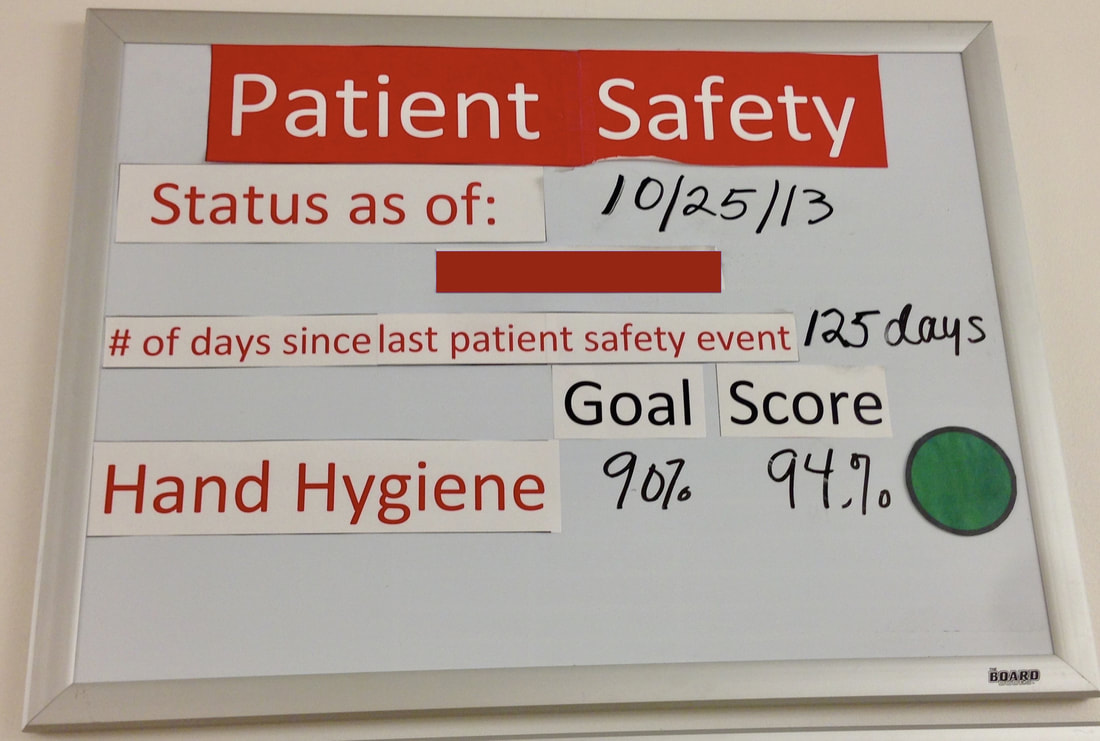

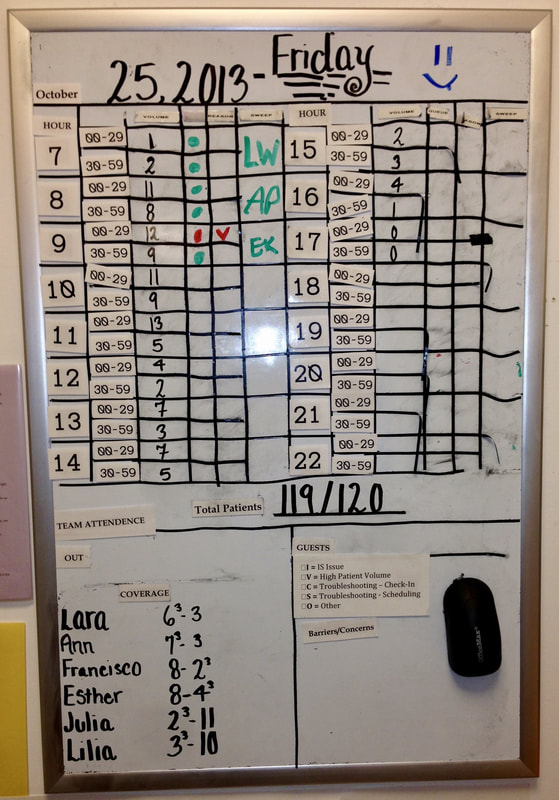

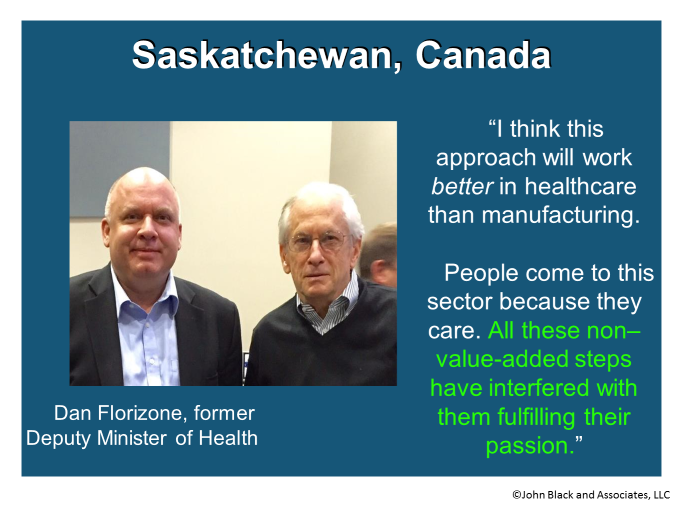

While consulting in Saskatchewan, initially some leaders doubted their ability to reach zero defects. Patients are not the only people at risk of harm from defects—healthcare workers are additionally at risk. They may be injured from lifting, slips, and falls. In order to overcome the mindset that zero defects is impossible to achieve, you need to eliminate the idea that these defects are inevitable. Preventable injuries are just that: preventable. But you need to put the proper measures in place. Unless zero defects is the goal, how can any healthcare system truly put the patient first and pursue continuous improvement?

To my mind, the only acceptable rate of preventable injury and death is zero.

In Saskatchewan, Suann Laurent, CEO of the Sunrise Health Region, demonstrated that she believes in, practices, leads, and mandates the goal of zero defects. She notes:

“I believe in what we call ‘Mission: Zero’—that safety is at the core of everything we do for our patients and with our staff. The more our culture of safety improves, the better our health system is for everyone we serve. For us, Mission: Zero means being defect free. Getting to zero defects is our goal.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed