Today I want to talk about why I’m passionate about this work. I want to talk about preventable deaths due to hospital errors. I want to talk about transforming healthcare so we can get to a mindset where, instead of feeling as though mistakes are “only human” and perfection is out of reach, ZERO preventable deaths are acceptable. We have a roadmap for this goal: Shingo’s Zero Quality Control.

Why is it when deaths happen one at time, there is less attention than when deaths happen in groups of 5 or 10, even if they add up the same? Fact: hospital mistakes kill enough people every day to fill two 747 planes. That’s as if we allowed two full 747s to crash, EVERY DAY, and did nothing! Every two months, it’s like 9/11 is occurring again. In anything else, we would not tolerate that degree of preventable harm. But in healthcare, we do!

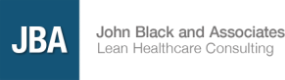

Unfortunately, statistics only say so much. Here are the real faces of a few medical errors in Canada, where JBA worked on the Saskatchewan Province hospital system.

Unfortunately, statistics only say so much. Here are the real faces of a few medical errors in Canada, where JBA worked on the Saskatchewan Province hospital system.

A 45 year-old Manitoba man died of a bladder infection in 2008 while in his wheelchair in a waiting room for 34 hours. No one even offered to help him when he asked or started vomiting. In 2013, a woman in Nova Scotia had a breast removed after a lab error mixed up her biopsy results with another patient’s. And this woman in Saskatchewan – after almost four years of agony and complications – insisted on diagnostic tests that revealed a piece of surgical mesh puncturing her bladder.

Examples are everywhere in the world. People being hurt or killed because of preventable mistakes. In one case a monitor was left on a boy’s finger during an MRI. Burned his finger to the bone. Another example: During routine surgery the doctor didn’t follow standard protocols. The patient bled to death – bled to death— during a routine procedure.

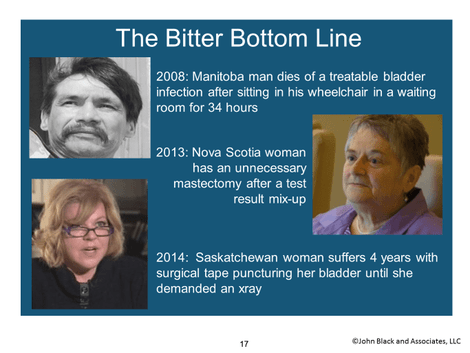

The World Health Organization shows that 1/3 to 1/2 of these medical defects can be prevented. Well, how? Through a systematic approach to patient safety that focuses not on people (who indeed may make misatkes), but on processes, which can be made mistake-free. Applying Shingo’s Zero Quality Control method of Poka-Yoke CAN deliver safer, higher-quality care. That’s how!

Examples are everywhere in the world. People being hurt or killed because of preventable mistakes. In one case a monitor was left on a boy’s finger during an MRI. Burned his finger to the bone. Another example: During routine surgery the doctor didn’t follow standard protocols. The patient bled to death – bled to death— during a routine procedure.

The World Health Organization shows that 1/3 to 1/2 of these medical defects can be prevented. Well, how? Through a systematic approach to patient safety that focuses not on people (who indeed may make misatkes), but on processes, which can be made mistake-free. Applying Shingo’s Zero Quality Control method of Poka-Yoke CAN deliver safer, higher-quality care. That’s how!

This is a famous Shingo quote. In particular the last sentence: “In contrast, a zero QC system pursues the active objective of eliminating defects.” Not just “reducing mistakes,” which implies that some (lower) level of mistakes would be acceptable. No, you MUST believe in and pursue the objective of zero defects.

When JBA got to Saskatchewan, we applied Shingo’s method to one of the most broken systems: surgery wait times. Waiting for necessary surgeries hurts patients’ health outcomes. At the time, the average wait for non-emergency inpatient surgery was 294 days, and 291 days for outpatient surgery. That’s almost 10 months. 4,000 people waited more than a year! This was not acceptable.

We achieved results by changing a culture that believed that waiting and mistakes were unavoidable. Our mistake-proofing training began by forming teams and selecting projects where direct harm had been caused to patients. Teams selected defects ranging from timely triaging of hospital emergency department patients to incorrect or insufficient cleaning of hemodialysis machines. Standard requirements included value stream maps and thorough patient/procedure quantity analysis. Each team then went on our week-long North American Tour. They studied and learned concepts at manufacturing and healthcare companies, all reiterating that zero defects WAS POSSIBLE. When they got home, the teams implemented corrective action plans. They collected defect data in 30-, 60-, and 90-day follow-ups, and utilized PDCAs and A3 thinking. Projects were not considered complete until they could report out a defect rate of less than a 1%, with 76% of projects reaching completion.

Achieving zero preventable deaths and preventable harm is possible. It is the moral obligation of all healthcare leaders from the top down in all of our major healthcare organizations and systems in America to lead this effort. I believe that our frontline caregivers are doing what they can within the system they have to protect patients but the current system isn’t working.

There are two leaders that have said it best, Atul Gawande and Donald Berwick, both MDs. In a quote from Gawande’s book “Checklist Manifesto” page 184:

When JBA got to Saskatchewan, we applied Shingo’s method to one of the most broken systems: surgery wait times. Waiting for necessary surgeries hurts patients’ health outcomes. At the time, the average wait for non-emergency inpatient surgery was 294 days, and 291 days for outpatient surgery. That’s almost 10 months. 4,000 people waited more than a year! This was not acceptable.

We achieved results by changing a culture that believed that waiting and mistakes were unavoidable. Our mistake-proofing training began by forming teams and selecting projects where direct harm had been caused to patients. Teams selected defects ranging from timely triaging of hospital emergency department patients to incorrect or insufficient cleaning of hemodialysis machines. Standard requirements included value stream maps and thorough patient/procedure quantity analysis. Each team then went on our week-long North American Tour. They studied and learned concepts at manufacturing and healthcare companies, all reiterating that zero defects WAS POSSIBLE. When they got home, the teams implemented corrective action plans. They collected defect data in 30-, 60-, and 90-day follow-ups, and utilized PDCAs and A3 thinking. Projects were not considered complete until they could report out a defect rate of less than a 1%, with 76% of projects reaching completion.

Achieving zero preventable deaths and preventable harm is possible. It is the moral obligation of all healthcare leaders from the top down in all of our major healthcare organizations and systems in America to lead this effort. I believe that our frontline caregivers are doing what they can within the system they have to protect patients but the current system isn’t working.

There are two leaders that have said it best, Atul Gawande and Donald Berwick, both MDs. In a quote from Gawande’s book “Checklist Manifesto” page 184:

"One essential characteristic of modern life is that we all depend on systems--on assemblages of people or technologies or both—and among them our most profound difficulties is making them work. In medicine, for instance, if I want my patients to receive the best care possible, not only must I do a good job but a whole collection of diverse components have to somehow mesh together effectively. Healthcare is like a car that way. In both cases having great components is not enough.

"Were obsessed in medicine with having great components—our best drugs, the best devices, the best specialists—but pay little attention to how to make them fit together well. This approach is wrong-headed. Anyone who understands systems will know immediately that optimizing parts is not a good route to system excellence. We give the example of a famous thought experiment of trying to build the world's greatest car by assembling the world's greatest car parts. We connect the engine of a Ferrari, the brakes of a Porsche, the suspension of a BMW, the body of a Volvo. What we get of course is nothing close to a great car; we get a pile of expensive junk.

"We have a thirty-billion-dollar-a-year National Institutes of Health, which has been a remarkable powerhouse of medical discoveries. But we have no National Institute of Health Systems Innovation alongside it studying how best to incorporate these discoveries into daily practice--no NTSB equivalent swooping in to study failures the way crash investigators do, no Boeing mapping out the checklists, no agency tracking the month-to-month results."

I am passionate about this work because I know we can do better. I know we use the Toyota Production System to save lives.

For more on how to achieve zero defects, check out my webinar here.

For more on how to achieve zero defects, check out my webinar here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed