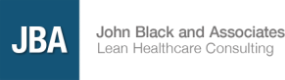

Back in the late 1500's, the Republic of Venice relied on rapid production techniques to survive. The Venice arsenal was produced by the largest industrial plant in the world at that time. The plant built warships. Because the Republic could not possibly afford to maintain a peacetime fleet large enough to repel attackers, it instead stood ready with the plant to literally build an entire fleet of ships on short notice--sometimes 100 ships in six weeks. It did this using techniques that were nothing short of enlightened, even by today's standards. The plant employed 1500 workers and covered 60 acres. It was the world's first large-scale assembly line. Necessity was the mother of invention. Reflect on that for a moment--better production techniques were used because survival--and victory--depended on it.

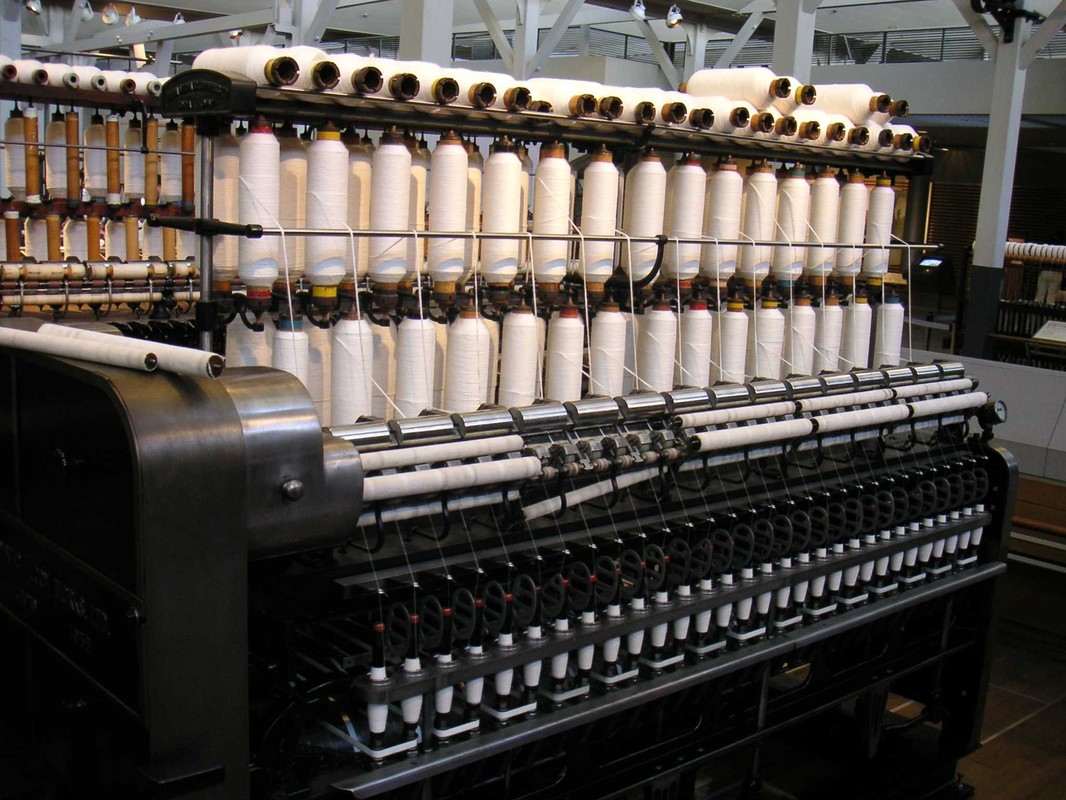

Two centuries later it was weapons again. Eli Whitney was awarded the contract to manufacture muskets for George Washington. A factory was built in New Haven, Connecticut. Some advanced production techniques were used: ordered integrated workflow; standardized, interchangeable parts; focused factory areas; dedicated machines; error-proofing mechanisms to reduce variations from personal craft. This example, too, is notable for the urgency that prompted innovation. America needed arms to protect itself in an era of international military conquest: better production techniques were used because survival--and victory--depended on it.

Still later, Henry Ford led a revolution of a different kind in this country. Ford can accurately be called "The Father of Cycle Time Management." Ford was a man who hated to waste time. In 1926 he wrote, "Time waste differs from material waste in that there can be no salvage. The easiest of all wastes, and the hardest to correct, is the waste of time, because wasted time does not litter the floor like wasted material." Between 1913 and 1914, Ford doubled production with no increase in the workforce. Between 1920 and 1926, cycle time was reduced by 90% from 21 days to 2 days.

The secret to Ford's success was a new process model for automobile manufacturing--Continuous Flow Assembly. And while his emergency was not a military one, remember that Ford was trying to build and dominate a brand new industry. He was quite literally trying to change the world. Like the other precursors of the JIT production system, better production techniques were used because survival--and victory--depended on it.

The secret to Ford's success was a new process model for automobile manufacturing--Continuous Flow Assembly. And while his emergency was not a military one, remember that Ford was trying to build and dominate a brand new industry. He was quite literally trying to change the world. Like the other precursors of the JIT production system, better production techniques were used because survival--and victory--depended on it.

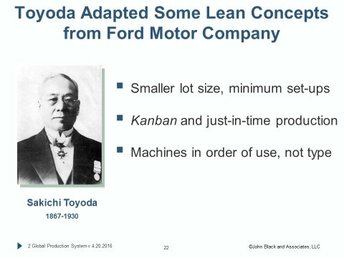

In 1949, Kiirchiro Toyoda sent his grandson to spend the summer at the Ford plant in Rouge. Soon thereafter, the Toyota system of manufacturing was born. To say that Toyota borrowed from Ford is not accurate. To say that Toyota copied Ford is not accurate. Toyota learned from Ford, especially from Ford's mistakes. The Toyota system was in some ways a revolution, just as Ford's had been. There were striking differences between how Toyota and Ford built cars. JIT was continuing to evolve.

One difference was that Ford relied on maximum lot sizes and minimum numbers of setups. Toyota, on the other hand, strove to reduce lot sizes to eventually produce each and every product uniquely.

Another big difference was in the control of production. Kanban was used as the major tool in Toyota's JIT production system.

A third key difference was in the rearrangement of equipment. Instead of grouping all machines together by type of machine--all of the lathes here, all of the milling machines over there, for example--Toyota arranged the machines in the order that they were used in the manufacturing process. This meant low inventories and small lot sizes.

These were revolutionary changes in automobile manufacturing. What prompted such innovation? Toyota was one of many Japanese manufacturers trying desperately to build something from what little was left of Japanese industry following World War II. Better production techniques were used because survival--and victory--depended on it.

We all know the result. Today, Toyota dominates the automobile market and is a model for manufacturing excellence. And Ford, the proverbial mentor, nearly failed before following the path of its protégé. The student became the teacher, and the teacher the student. In the school of hard knocks, Ford has learned a lot in the past decade, and better production techniques are being used because survival--and victory--depend on it.

One difference was that Ford relied on maximum lot sizes and minimum numbers of setups. Toyota, on the other hand, strove to reduce lot sizes to eventually produce each and every product uniquely.

Another big difference was in the control of production. Kanban was used as the major tool in Toyota's JIT production system.

A third key difference was in the rearrangement of equipment. Instead of grouping all machines together by type of machine--all of the lathes here, all of the milling machines over there, for example--Toyota arranged the machines in the order that they were used in the manufacturing process. This meant low inventories and small lot sizes.

These were revolutionary changes in automobile manufacturing. What prompted such innovation? Toyota was one of many Japanese manufacturers trying desperately to build something from what little was left of Japanese industry following World War II. Better production techniques were used because survival--and victory--depended on it.

We all know the result. Today, Toyota dominates the automobile market and is a model for manufacturing excellence. And Ford, the proverbial mentor, nearly failed before following the path of its protégé. The student became the teacher, and the teacher the student. In the school of hard knocks, Ford has learned a lot in the past decade, and better production techniques are being used because survival--and victory--depend on it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed