Some of the most brilliant minds and compassionate people go into healthcare. So why do we still see over 440,000 preventable hospital deaths every year? Question: do most healthcare leaders have a vision for their organization’s future? And have they “operationalized” it, as Dr. W Deming would say?

Vision separates “good enough” from “excellent.” Vision gives inspiration when the job gets tough. Vision makes the impossible, possible.

History shows this pattern: Vision comes first. Success follows.

In his research on the power of vision, Joel Barker came across a Dutch scholar’s work on successful civilizations. In Barker’s words, the scholar found this sequence of events, over and over: “First a compelling vison of the future was offered by leaders. Then that image was shared with their community and [the community] agreed to support it. Then, together acting in consort, they made the vision a reality.”

Today we see the same thing happening. Watch this video, about the difference between Detroit after it began to deteriorate in the late 20th century and Hiroshima, which was totally destroyed in 1945 and has been completely restored today.

Vision separates “good enough” from “excellent.” Vision gives inspiration when the job gets tough. Vision makes the impossible, possible.

History shows this pattern: Vision comes first. Success follows.

In his research on the power of vision, Joel Barker came across a Dutch scholar’s work on successful civilizations. In Barker’s words, the scholar found this sequence of events, over and over: “First a compelling vison of the future was offered by leaders. Then that image was shared with their community and [the community] agreed to support it. Then, together acting in consort, they made the vision a reality.”

Today we see the same thing happening. Watch this video, about the difference between Detroit after it began to deteriorate in the late 20th century and Hiroshima, which was totally destroyed in 1945 and has been completely restored today.

Hiroshima emerged from tragedy because its leaders promoted a positive, forward looking vision for the city. As the auto industry declined, American leaders abandoned Detroit’s future and its decay followed.

Lean gives us the tools to start setting our visions for healthcare. Imagine a future with zero wasted medicine, zero wasted steps to and from supplies. A future where doctors and nurses are able to spend more time with patients and less time on logistics. A future where healthcare is both financially solvent for healthcare facilities and affordable for the patient.

We need leaders to present the bold visions that lead to huge transformations. Change happens step by step, and commitment to the goal falters without clear inspiration. Healthcare needs a vision.

This isn’t fiction—lack of vision affects healthcare around the world today. Consider the recent cutbacks by the NHS in England.

Lean gives us the tools to start setting our visions for healthcare. Imagine a future with zero wasted medicine, zero wasted steps to and from supplies. A future where doctors and nurses are able to spend more time with patients and less time on logistics. A future where healthcare is both financially solvent for healthcare facilities and affordable for the patient.

We need leaders to present the bold visions that lead to huge transformations. Change happens step by step, and commitment to the goal falters without clear inspiration. Healthcare needs a vision.

This isn’t fiction—lack of vision affects healthcare around the world today. Consider the recent cutbacks by the NHS in England.

“An NHS body has suspended all hip replacements, cataract operations and other non-urgent surgeries for more than two months in an attempt to save more than £3 million…[the policy] will put about 1,700 people at risk of their condition worsening and leave many in pain.

Here’s the reaction from a U.K doctor about the rollback, and it’s spot on: “The CCG is trying to make short-term savings, which may have major consequences for patients. While patients wait for treatment, their conditions could deteriorate, sometimes making treatment more complex and costly. In addition, standing down surgeons and their teams is inefficient and a waste of scarce resources.”

Instead of doing the work to use their resources more efficiently, the NHS is making cheap cuts to their system, harming patients and employees.

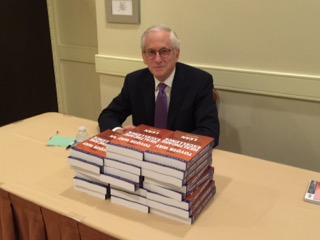

So what would a positive vision for healthcare look like? I want to point you to the work of Atul Gawande, M.D., best-selling author of The Checklist Manifesto, Better, and Complications.

Gawande lays out the only sustainable vision for healthcare I’ve seen to date:

Instead of doing the work to use their resources more efficiently, the NHS is making cheap cuts to their system, harming patients and employees.

So what would a positive vision for healthcare look like? I want to point you to the work of Atul Gawande, M.D., best-selling author of The Checklist Manifesto, Better, and Complications.

Gawande lays out the only sustainable vision for healthcare I’ve seen to date:

“We have a thirty-billion-dollar-a-year National Institutes of Health, which has been a remarkable powerhouse of medical discoveries. But we have no National Institute of Health Systems Innovation alongside it studying how best to incorporate these discoveries into daily practice---no NTSB equivalent swooping in to study failures the way crash investigators do, no Boeing mapping out the checklists, no agency tracking the month-to-month results.”

Our healthcare system has a good product; our doctors and nurses on the front line deliver the best care with the best medical technology available. But systemic waste gets in the way of their jobs. Healthcare leaders have got to invest in operations that streamline the care process with the priority of eliminating preventable deaths and mistakes with no compromise.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed